Blog

October 2, 2025

Minds Behind the Masterpiece: Arthur Laurents

When New York magazine reached out to Once Upon a Mattress composer Mary Rodgers Guettel in 2009 to get a comment on her friendship with American playwright and director Arthur Laurents, she told them to “call me back when he’s dead.” By then, Laurents had cut ties with her, as he frequently parted ways with those who did not agree with him or participate in his grudges. Numerous others crossed paths with Laurents and subsequently wanted nothing to do with him. This earned Laurents a terrible reputation in the theater realm, leading fellow playwright and close friend Larry Kramer to deride him as “a mean, ornery son of a bitch.”

His reputation was likely well earned. For example, when Patti LuPone planned to honor the late Jerome Robbins during the 2008 revival of Gypsy. Laurents chose not to participate in his departed friend’s tribute because he didn’t want to “share applause with a dead man.”

What makes this behavior more surprising? Despite the way he treated people, Laurents’ work focused on themes of social pressure, injustice, love, integrity, and friendship.

While we don’t know why he was so ornery, we do know that he was also on the receiving end of mistreatment during his career. After selling the rights for his play Home of the Brave to be made into a motion picture, Laurents was then hired to rewrite a screenplay by Frank Partos and Millen Brand for The Snake Pit. Laurents made sweeping changes to the script, but the original screenwriters claimed that Laurents hadn’t changed anything; they falsified drafts reflecting his changes and claimed they wrote them. Unfortunately for Laurents, he had not kept his own drafts, and his credit on the movie was removed. While Brand would later confess to what he and Partos had done, the event likely made one thing clear to Laurents: don’t trust anyone but yourself.

When Laurents was blacklisted for supposedly having communist and left-leaning politics, he only had himself to trust at that moment. This could easily have been the end of his career; even a superstar like Charlie Chaplin had his career derailed by being blacklisted.

What saved Laurents’ career? With his usual tenacity, Laurents took action, including writing a letter to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), that painstakingly revealed all his political beliefs in full detail. HUAC quickly found that he was too idiosyncratic and divisive for him to be a member of a single political group, and he was subsequently removed from the blacklist.

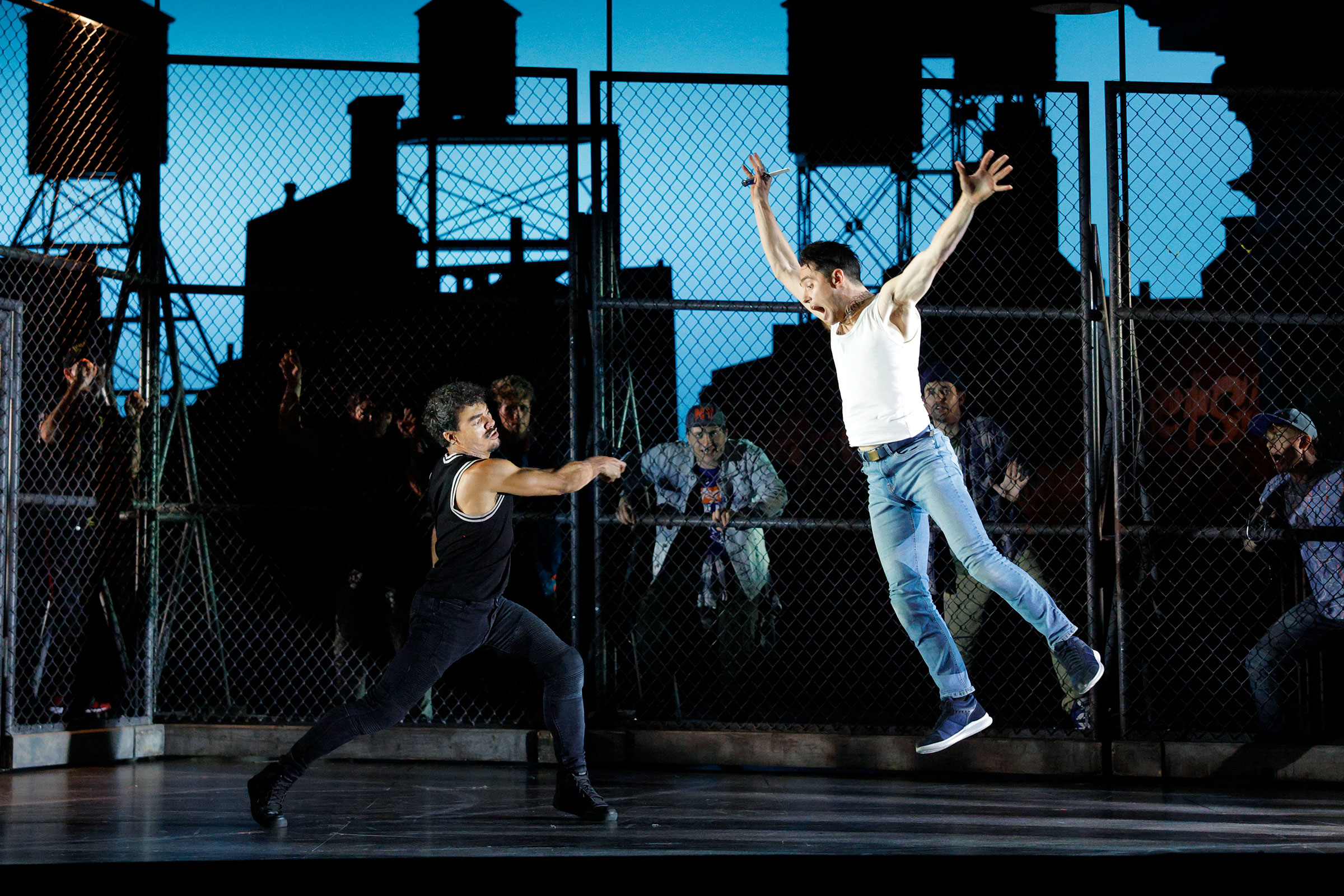

What Laurents apparently didn’t learn from his own experiences was to treat others with compassion. His behavior would become especially notorious during the creation of West Side Story. Director/choreographer Jerome Robbins and composer Leonard Bernstein were also opinionated geniuses—and they weren’t always the easiest to work with either. When Laurents was added into the mix, the resulting clashes would become the stuff of Broadway legend.

Rumors were that Laurents urinated on the musical’s sets to assert his dominance and drenched himself with milk during meetings. These stories are almost certainly false, but it does make one wonder what his actual behavior was like for people to have believed them. It is certainly true that his relationship with much of the West Side Story creative team was fractured by the end of the experience. Lyricist Stephen Sondheim said of Laurents: “It’s when you’re miserable that he’s at his best, if you’re happy or, especially, successful—watch out.”

You didn’t even have to work with him to have felt his wrath, in his 2000 memoir Original Story By he would include plenty of jabs at directors Robert Wise, Harold Clurman, and especially Sam Mendes. The basis for these jabs? He just didn’t like the way they directed. For Mendes in particular he detested his 2003 revival of Gypsy and used the musical’s lyrics to describe his feelings toward Mendes, “You either got it or you ain’t, and he didn’t got it.”

Towards the end of his life, Laurents did not have many friends, and the publicity about his jabs and quarrels led people to avoid him. The few friends that he did have he treasured and held close. But he didn’t shed any outward tears for the friendships that ended. Of all the things Laurents treasured, the most important was living his truth.

So what if he lost a few friends he didn’t see eye to eye with? He knew which ones truly loved him, like his lifelong partner Tom Hatcher who stayed by his side for 52 years until Hatcher’s passing in 2006. Laurents' life may seem tumultuous and lonely, but by all accounts, he was perfectly fulfilled, happy, and content with his legacy, hard as it may be to believe.

Even 14 years after his passing, Laurents remains a complicated figure in the theater world with many seeing him as a poster child for theater’s golden age of bad behavior and others seeing him as misunderstood. Yet his impact is undeniable; his art produced classics like West Side Story and Gypsy. Despite his behavior, we hope that his art can continue to bring people together for as long as it remains timely.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)