Blog

June 10, 2024

Queer Representation in Opera

Last year during Pride Month, we highlighted queer composers of the past and present to help shine a light on their contributions to the opera world. While it’s important to highlight the real people behind the works we present, it’s also important to bring attention to how queerness is represented on stage. For most of opera’s history, there was little to no queer representation onstage, but the past couple of decades has seen a major influx of representation in sexual identity. For this year’s Pride Month, join us as we journey through the history of queer opera characters.

For centuries, queer characters in opera were incredibly rare. In fact, between opera’s conception in the 16th century and the 20th century, we can only find one opera that might contain queer coded characters: Christoph Willibald Gluck’s 1779 opera Iphigénie en Tauride and the characters of Oreste and Pylade. While Gluck may not have specifically intended for these characters (drawn from Greek mythology) to be queer, Orestes and Pylades had been presented as such by some authors during the Roman era. Couple this with their intensely intimate relationship and lack of romantic interest in women, and you can why many directors have staged the opera as if the two were lovers.

We’ll also briefly mention Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 1879 opera Eugene Onegin. The opera may not have been originally staged with the titular character’s struggle with his homosexuality in mind, but as biographers learned more of Tchaikovsky’s life, many have come to consider the opera as his way of writing about his own gayness. This has led some modern stagings of the opera to lean more into how Onegin’s sexuality impacts his possible romantic relationship with Tatyana.

Fast forward a century and a half later after Iphigénie en Tauride’s premiere and you’ll find the first openly queer opera character in Alban Berg’s Lulu. The opera premiered in 1935 (though it wasn't staged in a complete version until 1979) and contains the character Countess Geschwitz, a lesbian character in love with the title character. It’s not the most romantic relationship, as Lulu wants nothing to do with her and mistreats her, but the Countess cares so much for Lulu that she puts her own life on the line for her sake. At the end of the opera (spoiler alert!), both Lulu and the countess are murdered by Jack the Ripper. In her final moments, the countess sings of her love for Lulu. It’s sad that the first explicitly queer character in opera meets a tragic ending, but, well, that seems to be the case for so many of the characters in our most beloved operas.

In 1951, Benjamin Britten's Billy Budd (performed by LA Opera in 2000 and 2014) brought what one scholar called "overtly subtle" gay themes into opera houses worldwide. Taking place almost entirely aboard a British navy ship, with an all-male cast, the opera depicts the downfall of an angelic sailor, praised for his beauty, by a closeted officer who becomes obsessed with him. This opera is also notable for the fact that Britten himself was an essentially openly queer composer.

Fast forward a couple more decades later to 1970, and we find a gay male couple in Sir Michael Tippett’s The Knot Garden. Unlike the one-sided romance in Lulu, this pairing is a mutual one. For context this opera premiered three years after homosexual acts between two consenting adults became legal in England. The 70s would also see the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s final opera, Death in Venice, which brings tragedy back in full force with Aschenbach, the gay leading character of the opera, dying before he’s able to express his love to the youth Tadzio. Based on the novella by Thomas Mann, this was Britten’s dream opera that took years to adapt.

A rise in queer representation in opera notably led to Leonard Bernstein's 1983 opera A Quiet Place, which includes a gay couple among its characters. But the trend then dwindled, perhaps because of a more conservative America along with the rise of the AIDS epidemic. Interest in queer stories would return in the 90s. Tony Kushner’s essential queer play Angels in America, which tackled the AIDS epidemic amongst numerous other American issues, arrived on Broadway in 1993. The play was a huge success and opened the minds of many theatergoers to queer stories, and this interest would translate to opera as well. Two major operas with queer representation from the 90s are Stewart Wallace’s Harvey Milk in 1995 which adapted the life and romance of the famed San Francisco Supervisor and Paula M. Kimper’s Patience and Sarah in 1998, which saw opera’s first lesbian relationship and achieved mainstream success.

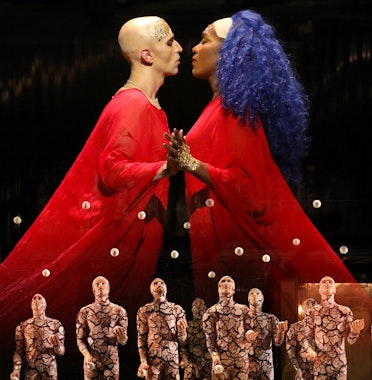

These operas would set the stage for queer stories in the new millennium, with operatic adaptations of essential queer stories like Peter Eötvös’s Angels in America and Charles Wuorinen’s Brokeback Mountain. In recent seasons, Terence Blanchard's queer-themed operas Champion and Fire Shut Up in My Bones have both been big hits at major American opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera. Other queer operas of note include Matthew Aucoin's Crossing (presented by LA Opera in 2018), Emma O'Halloran's TRADE (presented by LA Opera in 2023), Rufus Wainwright's Hadrian, Jake Heggie’s Three Decembers and For a Look or a Touch, Jorge Martín’s Before Night Falls and Gregory Spears’ Fellow Travelers. Queer representation in opera would expand even more with Laura Kaminsky’s As One in 2014, which shows the transition journey of a transgender woman.

Queer representation in opera is constantly growing, and it’s gratifying to see a surge of queer stories come to the stage. With opera’s long history of queer composers, it’s only right that queerness should be represented on stage. It’s vital that these stories be told to keep the art form alive.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)