Blog

May 22, 2025

Inside the Wardrobe of "Rigoletto": A Conversation with Costume Designer Jessica Jahn

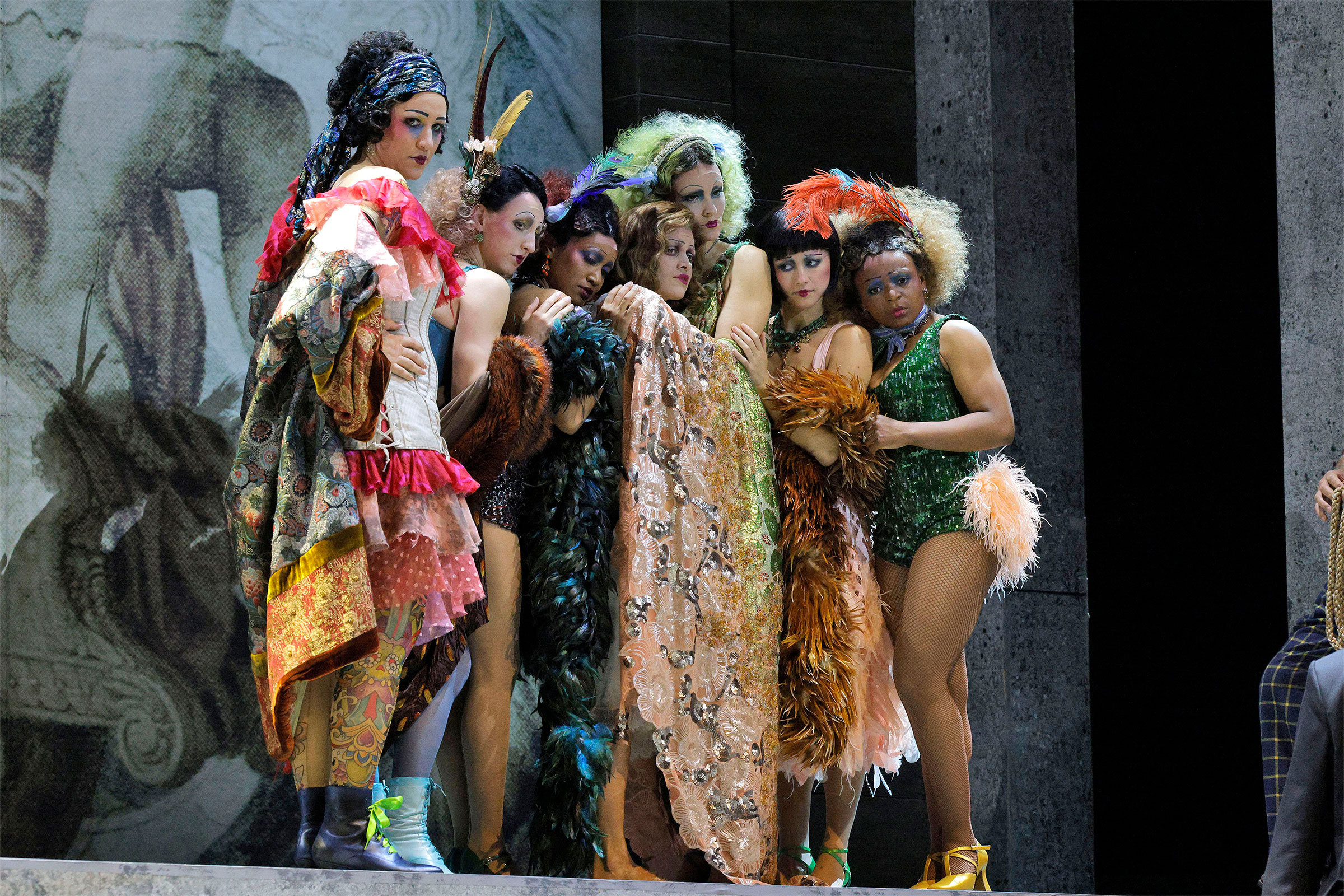

One of the most dazzling aspects of our production of Rigoletto is the breathtaking costume design that transports Verdi’s timeless characters to 1920s Italy. These striking looks are the work of the brilliant Jessica Jahn, whose unconventional path to costume design is as captivating as her creations. From dancer to psychology graduate, and now pursuing a degree in cultural anthropology, Jahn brings a unique perspective to every stitch and silhouette. In this exclusive interview, we step inside her world to discover the inspiration and intention behind her extraordinary designs.

Verdi’s operas are celebrated for having psychologically rich characters, as he often adapted from some of history’s greatest writers. With your background in psychology, how do you go about portraying the complex interior worlds of these characters in their outfits?

That’s a great question! In this story, no one is as they seem at first glance, or to each other—even our title character is cloaked in an irrational disguise, hiding who he is from those closest to him. The continuing display of dishonesty and masquerade for entertainment’s sake, or worse—to take advantage of another—makes it difficult to interpret any of the characters’ rationale. The idea of masks, then, both literal and figurative, is present throughout the work, and through my visual aesthetic. From the masks presented to the courtiers at the party that are then used for the kidnapping of Gilda, to the grotesque makeup of Rigoletto and the other characters, the horrifying environment onstage starts to be revealed as the layers of disguises come off. Some of these changes are made in front of the audience, avista—and some are inferred, as we realize that money and excess can have the power to hide our inconvenient true selves. We can physically follow Rigoletto and Gilda, and their journey, as their illusions of the world fall one by one.

On top of psychology, you also have a background in dance, and your work has often taken the movement of the actors into consideration. With opera singers, it’s of course important to make sure they feel they have control over their body. How do you go about ensuring that your vision is met while also taking into consideration the singer’s needs?

Funny enough, I actually just had a conversation about something similar with a singer and colleague of mine when talking about the design process. What I ended up saying to him was that when it comes down to it, the singer—as both a performer and an athlete (much like a dancer)—needs to have access to and control of their body. It is their instrument; it is what they are gifting to us as an audience.

What that means for me, as a costume designer specifically, is that a large part of my job is supporting that; I am supporting their instrument. So, going into a design, I am already making sure that I am thinking about their body in the same way that I would think about a dancer’s body—there should be room for expansion, movement, air. In a way, my design comes “second.” (Don’t tell anyone that I said that, ha!) You have to be slightly egoless when it comes to a design. The intent of the story is your scaffolding and structure—so that if the design needs to change for a body or a voice, it can do so without affecting the storytelling. Whether a garment is a certain style or structure, or color doesn’t really matter—if the intent of the garment and the story it is telling stays the same. Then, it becomes easy to accommodate for any performer and each of their individual needs.

Rigoletto is a story that depicts the class struggle and the suffering that comes to lower-class civilians at the hands of the upper class. Can you go into detail on your approach to visually distinguish the “one percent” in the story and the lower-class civilians?

Rigoletto is inherently a difficult piece. Within the story are ideas and images of brutality, misogyny, and rage, and people (especially women) are treated as social and emotional fodder. It is an uncomfortable piece to look at head-on. There isn’t even a righteous moral at its conclusion—as the curtain falls, the persecutors are left to continue on seemingly unaffected.

Instead of shying away, as a production team we recognized that this is actually the perfect time and place in our history to tell such a story. Much of today’s world seems to be a mirror of Rigoletto’s. When we look at our nation’s current stories of extreme excess, callousness in the face of human need, and overt misogyny in our leadership—it seems that the issues presented to us by Verdi haven’t changed.

While we as a team knew inherently that we were not interested in setting our story in the present—we also knew how important it was to provide a platform that would mirror both the world of Verdi, as well as the current social climate. It didn’t take long to recognize that the cultural upheaval and zealous nationalism during the beginning of Mussolini’s control of Italy in the 1920s and ’30s would be the ideal setting—providing historical context as well as looking toward our own future.

Visual motifs often carry deep symbolism in costume design. Were there any specific symbols, textures, or color palettes you used repeatedly in Rigoletto to hint at emotional or thematic undercurrents?

I was struck by the visual and social connection to the art movements of the time—many of which grew out of a direct reaction to the war. The iconic images by artists like René Magritte, Max Ernst, and Otto Dix seemed uncannily accurate to the complexity of the story. The artists from this art movement and period seemed to have an uncanny relationship and direct visual nod to our story, and we recognized that we could then embody an iconographic archetype that represented the underlying dramaturgy of Rigoletto.

These surrealists provided us with a perspective on the period that is both beautiful and grotesque—their images are wrought with contrast and dichotomy. The breadth of their work presents us with the abstraction, vulgarity, and dystopian identity that we feel is essential to the story. Opulence against extreme loss, the wholesome against the vulgar. By using the paintings as guides for tone, clothing shape, and color, we can give a sense of heightened realism to match the music and libretto. This concept can also provide the platform needed to create a sense of timelessness and help make the story more relevant to a modern audience—without the need to put everyone in contemporary dress.

Opera is a medium rooted in tradition, yet modern productions often push boundaries. How do you strike a balance between honoring historical context and bringing a contemporary lens to a work like Rigoletto?

Once we had landed on our aesthetic universe, I went about shaping our characters—by twisting time period and pushing visual boundaries. By giving respectful nods to fashion designers such as John Galliano, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Alexander McQueen—I was able to additionally incorporate visual cues for a modern audience. This is something that, though not always necessary in a design, sometimes helps to convince the viewer that what they are seeing is real—that they are immersed and fully involved in the universe we have created and can be drawn into the emotional arc of the story we are creating.

This style of pushing the surrealist Dix aesthetic—creating tension, color, abstraction, and a sense of heightened realism—helps to make the storytelling more dynamic. Using this framework, we continued to add and use inspiration from these designers, and others like them—who were also so good at extrapolating the “feeling” of the extravagance during this period. The world we created wanted to feel both sumptuous and grotesque all at once—so that it left the audience visually and emotionally satiated.

In many ways, costume designers are visual storytellers. How do you collaborate with the director and other departments—like set and lighting design—to ensure the visual world feels cohesive?

This is going to be my shortest answer ever—and maybe the most concise: communication! There is no way to collaborate with any other part of the production process (and this includes all company members) without respectful and honest communication about ideas and overall objectives. My favorite and most effective design processes have been the ones in which the entire director/design team, the production company, and the performers were in open communication about the intention of the storytelling from the very beginning. It’s an exhilarating feeling.

With your ongoing studies in cultural anthropology, how has that field reshaped the way you view character, society, and costuming as a whole? Has it influenced your interpretation of Rigoletto in particular?

Oh, that’s interesting—let me think. To be honest, I actually think that the reverse is true: that my design career has always been influenced by my interest in, and extracurricular study of, anthropology, sociology, and history. The things that resonate with me about my job as a storyteller are the ways in which our lives intersect with the past, with our shifting social communities, with our collective futures. So, when I am thinking about how each production, each story that we decide to tell, reflects those landscapes—that’s when and where I get excited about how my costume work can fit in.

In reality, I don’t think that we can do what we do without that type of curiosity and knowledge. The very fact that my team and I can understand the historical foundations of Rigoletto, draw parallels in both the past as well as the present, and can potentially foresee the “future” within Verdi’s piece—that is the groundwork for any social science as well as any honest and holistic artistic endeavor, regardless of its form.

If you want to see Jahn’s costumes in person, click here to get tickets to Rigoletto.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)